Review by Prof Tinyiko Maluleke, Vice-Chancellor and Principal

VC Book of the Month

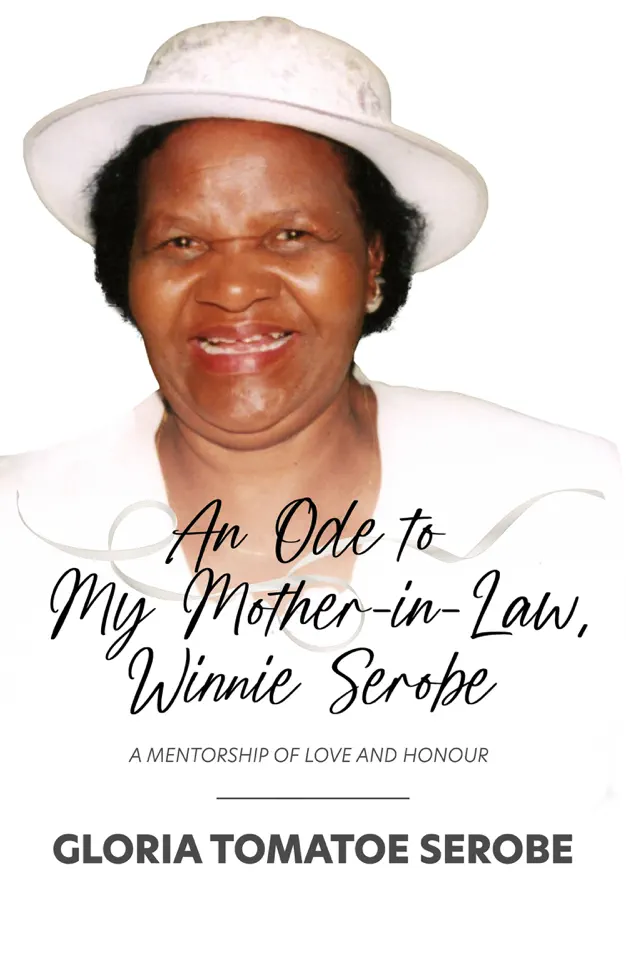

Gloria Serobe, An Ode to My Mother-in-Law, Winnie Serobe. A Mentorship of Love and Honour. Johannesburg: Tracey McDonald, 2023, 152pp

“This book is dedicated to a woman who held my hand with warmth, nurtured my heart with love and led me to a path of family love … That woman is my mother-in-law, the late Mrs Winnie Serobe.”

Prof Tinyiko Maluleke, Vice-Chancellor and Principal with Dr Gloria Serobe, author of an Ode to my Ode to My Mother-in-Law, Winnie Serobe.

Thus reads the dedication and declaratory page of Gloria Serobe’s book. In his foreword to the book, Gaur Serobe - husband of the author and son of the subject of the book - suggests that this book is about “an ordinary love between two exceptional women, an ordinary bond between two women that I love deeply” (p. xv). However, when one reads the whole book of 152 pages, drinking it all in; when one considers the fortitude with which Winnie Serobe (née Radebe) struggled against the Apartheid-imposed limitations which she was up against, one must conclude that there was nothing ordinary about either Winnie Serobe or Gloria Serobe (née Ndaliso). Not even the word ‘extraordinary’ – which Gaur Serobe – later introduces, completely captures the relationship between the woman from Matukaneng ko Thaba ‘Nchu’ – the late Mme Mma Winnie Serobe a.k.a ‘Sinky’ and her daughter-in-law, Gloria Serobe.

This book takes on and seeks to overturn aspects of global and African cultures which are steeped in centuries of myths, fables, legends and children stories built around the character of the wicked mother-in’law – the “mother-in-law from hell”.

This character is the butt of jokes, the target of stigma and the object of vendettas. The only character as tarnished as the “mother-in-law from hell” is the “stepmother from hell”. The reason so much hate is directed at the mother-in-law is simply because she is a woman. In most cultures, there is neither myth nor equivalent stereotype of a “father-in-law from hell”.

If only the myths of the “evil mother-in-law” were a matter of history and ancient cultural mores. If only these myths were confined to a few cultures. But no. These myths and stereotypes remain very much alive, across many cultures. They are aspects of patriarchy, drivers of misogyny, and they intersect and overlap with other forms of bigotry, including racism and various forms of economic and cultural exclusion.

For these and many related reasons, we must refuse to take this little book of Gloria Serobe at face value. Yes; it is an appreciative memoire-biography of Mrs Winnie Serobe. But, in my view, it is much more than just a biography. Yes; the book is an appraisal of a phenomenal woman and a distillation of lessons learnt from her – but it is much more.

In the book, the history of the Serobes as well as their maternal and paternal ancestries are outlined. But I suspect that what we have in this little book is much more than an expanded or conventional family diary. The twenty-six chapters of the book, packaged into five bundles or parts; are brief but punchy, strategically approached, purposefully unfurled and the stories therein are told in evocative and thought-provoking ways.

Yes; this is a book about “an ordinary love between two exceptional women, an ordinary bond between two women…” but no, this is much more than an inward-looking feel-good story of an outlier daughter-in-law and an outlier mother-in-law whose experiences were only a flash in the pan.

For me, this is a book about the evolution of the black South African family and its struggle to overcome the limitations of both black culture and the economic stranglehold of Apartheid. The many memorable and delectable interactions, encounters and ventures of a daughter-in-law and mother-in-law captured in the book notwithstanding, I suspect that this book is much more than merely a manual either about ‘daughter-in-lawship’, ‘mother-in-lawship’ or ‘good-wifeliness’. We must not let the beautiful mother-in-law/daughter-in-law-story told in the book deceive us into thinking that this is an apolitical book. There is an unspoken harder core to this book. The story of Winnie Serobe (and Gloria Serobe) is the story of the socio-political condition of the black woman in both urban and rural South Africa in late 1980s up to the first decade of the 21st Century.

In her preface to Ellen Khuzwayo’s standard-setting classic – Call Me Woman – Nadine Gordimer commented that, “perhaps the most striking aspect of this book is the least obvious. It is an intimate account of the psychological road from the old, stable, nineteen century African equivalent of a country squire’s home to the black proletarian dormitories of Johannesburg” (preface to Call Me Woman, p. xi). In similar fashion, the ‘least obvious aspect’ of Gloria’s Serobe’s book is that it is not just the story of one woman. It is the story of “a woman who was connected to the South African psyche and that of black people in particular” (p.56). Winnie Serobe was a woman in touch with pulse of black life, its exigencies, its vagaries, its ups and its downs. A book that reflects on her life necessarily also reflects on black life, especially the condition of the black woman.

The book contains many brief but fascinating portraits of icons other than its declared and central subject. Consider the character of Gaur Radebe – grandfather of Gloria’s husband who was named after him. Gaur Radebe was the only other black person at Sidelsky’s Jewish law firm at which Nelson Mandela articled. Amongst many other prominent roles, Gaur Radebe, like Walter Sisulu was mentor to young Nelson Mandela. Consider Moses Mauane Kotane – former Secretary General of the South African Communist Party and former Treasurer General of the ANC. He was married to Rebecca; Winnie Serobe’s sister.

Winnie Serobe was a force of life. There are not many mothers-in-law who will go searching and choosing for a wedding dress with and for their daughters in law. Winnie Serobe not only did that, but she also paid for her daughter-in-law’s wedding dress. Some mothers-in law may take time to teach their daughters-in-law how to do domestic chores – and Gloria Serobe was “not that strong in house chores” (p.29). Instead, Winnie Serobe mentored, networked and enlisted her daughter-in-law into volunteerism and community service in order to create a more equitable society.

How many mothers-in-law will take their daughters-in-law to the meetings of the YWCA, Ikageng Women’s Club, Black Consumer Union, Housewives League, the South African National Council for the Blind? How many mothers-in-law will introduce their daughters in law to the Ellen Kuzwayos, Joyce Serokas, Sally Motlane, Nonia Ramphomanes, Albertina Sisulus of this world? How many mothers-in-law will school their daughters-in-law in the strategies and tactics for mobilising ‘the poor to help the poorest’ (p.81).

Some fathers-in-law are more helpful than others. But not many fathers-in-law will take it upon themselves to teach their daughters-in-law how to drive on the correct side of the road. Andrew Serobe did.

While this may appear to be a book about how a mother-in-law taught a daughter-in-law how to be a good bride and how ‘build a home’, the book also sharply poses the question “why women have to carry this responsibility – almost on their own (p. 104). This is a book whose author, together with other women, established “a retirement Umbrella Fund for Domestic Workers with Old Mutual in December 2007” (p. 97), and got employers of domestic workers as well as other players in corporate South Africa to contribute to it.

It is remarkable that in this book of 152 pages, the author only begins to write, rather briefly, about herself, on page 91 of the book. And the little that she writes about herself is framed as her humble attempt to multiply her mother-in-law. And yet Gloria Serobe is a respected South African community builder in her own right. She established the Greenhouse Child Care Center for young mothers – a seven days a week facility with a 24 hour accommodation option. And guess who came back from retirement to assist with running the centre? Mother-in-law Winnie Serobe.

In 1992, Gloria Serobe was awarded the Eskom Woman of the Year for the most innovative community project. And guess who else was honoured on that occasion? None other than the indomitable and inimitable Ellen Khuzwayo, who received the Lifetime Achiever Award. When she was asked by President Mbeki and the leaders of 58 non-governmental organisations both to join and chair the Presidential Working Group for Women, Gloria Serobe felt validated and energised. All these accolades were showered on Gloria Serobe when her mentor and mother-in- law, Winnie Serobe, was still alive.

But perhaps her greatest sense of self-actualisation, came when Gloria Serobe, together with other women, “set out to confront [Eastern Cape] poverty head on” (p.103). In part, that is how and why WIPHOLD was born. WIPHOLD went on to prove, amongst other achievements that “large scale commercial farming can be financially sustainable on communal land” (p.101). After four of the shortest chapters in which she briefly showcases the kind of work her mother-in-law inspired her to accomplish, the author swiftly returns to the subject of the book – her mother-in-law. Lyrically and with a palpable sense of appreciation, Gloria Serobe describes the legacy of her mother thus:

… we may not find the name of Winnie Serobe in any of the country’s annals of history. But you will find her name on the lips of her children, for whom she sacrificed everything to ensure they were taken care of, nurtured and educated. You will find her name on the hearts of the young women she encouraged to make different choices that changed the trajectory of their lives forever. You will find her memory in the community of Diepkloof and others, where she worked so tirelessly to make a difference to the lives of ordinary, vulnerable, and sometimes ‘unseen’ people (p.68).

Can a daughter honour a mother better? Can a daughter-in-law show gratitude to her mother-in-law more intensely? Can a woman honour a fellow woman more profoundly? Can a human show deference to another more splendidly? I doubt.

An Ode to My Mother-in-Law, Winnie Serobe. A mentorship of Love and Honour by Dr Gloria Tomatoe Serobe.